We’ve had a rather dramatic home lately. I hate it. Still, I guess that there’s one perk: parenting multiple children is good preparation for writing characters.

I’ve been meaning to do more creative writing–that was part of why I reduced this blog, really. The truth? I haven’t done much. But when it comes to thinking about characters, I know that as a reader, how I feel about the characters has a huge impact on how I feel about the whole book. If I don’t like any of the characters, I don’t like the book (I’m talkin’ to you, Madame Bovary! Also, come to think of it, Twilight). But if I love the characters, or if the author gives me enough information to make me empathize with the bad guys, that’s a huge part of what makes me love a whole story.

Watching my daughters interact sometimes feels like reading a book that’s become frustratingly predictable. Each of the two protagonists are uniquely lovable, but their vastly different personalities and character traits lead to misunderstanding and heartache, seemingly at every turn. I enter a scene, catch a snippet of dialogue, and I know both how and why it’s going to play out, yet I feel powerless to stop it.

Here’s an example: J comes downstairs from bed. She’s noticed that our neighbors walked into their house and left a door open. She’s concerned, so she comes downstairs to let me know. M’s with me in the kitchen, and you can see J hesitate. I can see the little wheels turning in her head. Is she being silly about the door? She expects that somehow M’s going to tell her that she’s wrong or make fun of her, but she’s worried. How can she sleep while she’s fretting about her neighbors? So, quietly, she asks me. But it takes me a few minutes to figure out what she’s talking about because she’s trying to speak quietly so that M won’t notice her. Which is entirely the wrong course of action, because of course a conversation that’s intended to be quiet and private becomes instantly more interesting to M, who proceeds to hover. And I start to shoo her away until I realize that J’s not asking anything embarrassing or private: she’s just concerned about her neighbors. Which is nice. I assure her that the door is broken or something, because it’s often left ajar. No worries. J has a hard time taking “no worries” for an answer. Like, ever. I say it again, more emphatically.

This is when M starts to chime in, too. She’s trying to help by backing me up: that door is open all the time–hasn’t J noticed? It’s true. At which point I’m shaking my head at M: butt out, butt out. Whether it’s her intention or not (hmmm?), M joining me in telling J that there’s nothing to worry about just fulfills J’s fear of speaking up from the beginning. To J, it sounds like M is telling her that she’s stupid. It sounds a bit like that to me, too. But this is exactly the sort of critical tone to which M appears to be entirely immune. I think if J and I both told M, point blank, that she was stupid, M would laugh it off and say, “Are you kidding? I’m brilliant. Seriously, I’m, like, super-smart.” So does this make her tone deaf to how she sounds to all others, or does she dial it back for her friends? I’m not sure. In any case, at this point I’m telling M, “You’re not helping. You. are. not. helping.” And she was backing me up and telling J that she has nothing to worry about, so what’s the problem? The problem is that her mother is mean and hates her and wants her not to talk. Or, that’s her argument at this point. I have a terrible time gauging M’s sincerity. Have I mentioned this before? There was a famous time that she fake-cried her way to a trip to get ice cream that I thought I’d shared on the blog, but just now, I couldn’t find it. She’ll also argue just for the sake of arguing, like her lawyer father. So when she says that she’s just trying to help or when she says that she thinks I’m being mean to her, I have no idea if she’s making it up or not.

If you’re keeping track, I now have one child who feels Stupid and another one who feels Oppressed. Awesome.

At any given moment dealing with M, I’m trying to operate on multiple planes: the actual reality of what she’s saying and doing and how others perceive it, what M projects as her perspective, and what M is actually feeling, which may or may not be the same as what she’s projecting. I’m all for honoring feelings, as you know, but when your child is Mistress of the Fake Cry, it becomes quite difficult not to be manipulated at every turn while still being empathetic.

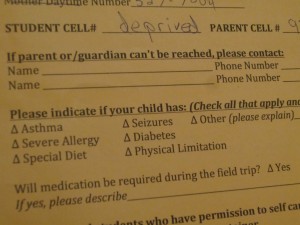

And dealing with J is just as frustrating, possibly more so. She had a valid question about the stupid door. She was being thoughtful and conscientious. Even if her sister thought that she was being silly, she wasn’t. But I just hate the way J chooses to communicate. She’ll say, “[sigh] I don’t know why I’m still hungry. I wish there was more to eat” instead of, “Can I please have some more to eat?” Or there’s a field trip coming up, and when I ask if she’d like it if her dad or I chaperoned, she says, “I bet Daddy can’t do it because he has to work.” Freaking irritating.

So I’m a broken record. M, consider your tone of voice and what you’re saying because not everyone is imbued with massive inner awesome that makes them invulnerable. J, you need to stick up for yourself and ask for what you want in life. And then I worry that my own perspective is so skewed on each of them that I’m responding to how they’ve acted the last 30 times instead of what’s actually happening at a new and unique moment.

Except that their characters are so consistent that these moments never feel unique.

Claire

You are hysterical! I have missed this type of post.

Katie

Aww, thanks Claire!